Balancing Schedules is Abject Chaos. Unless You’re Khoury College Professor Richard Hoshino.

Anyone who has attended college in recent years is extremely familiar with the process of course registration.

You pick out your classes in advance. You’re excited for the potential of the new semester, and you’re ready to register.

Your slot opens and … the class you needed for your major is full. You scramble to find a last-minute replacement, and thankfully, it turns out there’s another section. But now the backup section conflicts with an interesting elective that’s offered only once every two years. Your perfect schedule is shot.

For Richard Hoshino, associate teaching professor at the Khoury College of Computer Sciences in Vancouver, this isn’t a problem. It’s an opportunity.

Hoshino solves these kinds of issues—and many more—through scheduling optimization.

Scheduling optimization in a nutshell

High school students have tricky schedule concerns too; they spend four years taking specific classes to prepare for college. Coupled with fulfilling their high school general requirements, students find themselves in a difficult situation when the school registrar doesn’t account for their course preferences. This is where Hoshino swoops in.

“I think it’s extremely important to ensure that teachers can teach the courses they want, while maximizing students getting into the courses they need,” he said.

Hoshino’s goal is to enroll every student into all of their core courses, and as many elective courses as possible.

His most recent client was a high school that employed two teachers who were married to each other and were parents of a young child. Using Python, Hoshino created a rule in the code that these two teachers couldn’t teach in the same timeslot. Considering teacher scheduling preferences, class times, and many other constraints, Hoshino developed the school’s 2021-2022 master timetable.

Five hundred students made more than 2,900 course requests that semester. Hoshino’s master timetable satisfied all but twelve.

“Through my research, I’m able to solve these real-world problems,” explained Hoshino. “Then I’m able to achieve results like this, where I can get nearly every single student into every single one of their classes while satisfying hundreds of constraints that need to be met from the perspective of the school administrators as well as the teachers themselves.”

Those twelve students weren’t completely out of luck, though. Hoshino spoke to the school registrar, who found backup options for each of them.

Scheduling optimization isn’t just for school timetables though. Hoshino has also helped Nippon Professional Baseball, Japan’s top-flight league, slash their carbon emissions by creating a schedule that minimizes the distance that teams travel. On his work in Japan, he said, “It’s really exciting to see how math can be used in such elegant and surprising ways. During my three years in Tokyo, I became one of the world’s experts in a field called sport tournament scheduling.”

Governments can leverage scheduling optimization as well. In the case of the Canada Border Services Agency, Hoshino created an improved risk-scoring algorithm for marine cargo containers coming into Canada so the CBSA could forgo the common practice of geographical profiling—a method that judged the relative security of the cargo solely based on the export country. Hoshino designed the algorithm to consider the importer and exporter’s prior business transactions, the freight forwarder’s criminal record, and the transported item’s origin not logically fitting with the country it supposedly came from, among others. These factors are risk indicators for cargo ships that may be carrying weapons or drugs.

Hoshino explained, “It was quite exciting to use techniques in machine learning—and techniques in data mining that we teach at Northeastern—to help design algorithms that led to improved rates of drug and weapon seizures, with no geographical profiling.”

As the owner and principal of Hoshino Math Services, he runs professional development workshops for high school teachers and math workshops for students. The bulk of his consulting work is in using his expertise and scheduling optimization to create timetables for businesses and schools. His endeavors landed him the Adrien Pouliot Award—the Canadian Mathematical Society’s recognition of sustained, significant contributions to Canadian math education. Oh, and he’s the youngest winner in the 26-year history of the award.

From practice to pedagogy

So how did Hoshino land at Northeastern? He stumbled across an article about the university’s new Vancouver campus and was immediately drawn to it. “I became very attracted to the Align MSCS program whose values and mission were amazingly parallel to my own and what I wanted to do as an educator.”

During the summer of 2021, Hoshino taught a math prep course to nearly 100 incoming Northeastern students across Northeastern’s campus network. On the course, he enthusiastically remarked, “In this math prep course that I’m teaching right now, I’m working with a paralegal, a nurse, a welder, a lawyer, and several U.S. Army veterans. It’s just so exciting to have such a diverse array of life experiences in the classroom. That’s what attracted me to teach at Northeastern.”

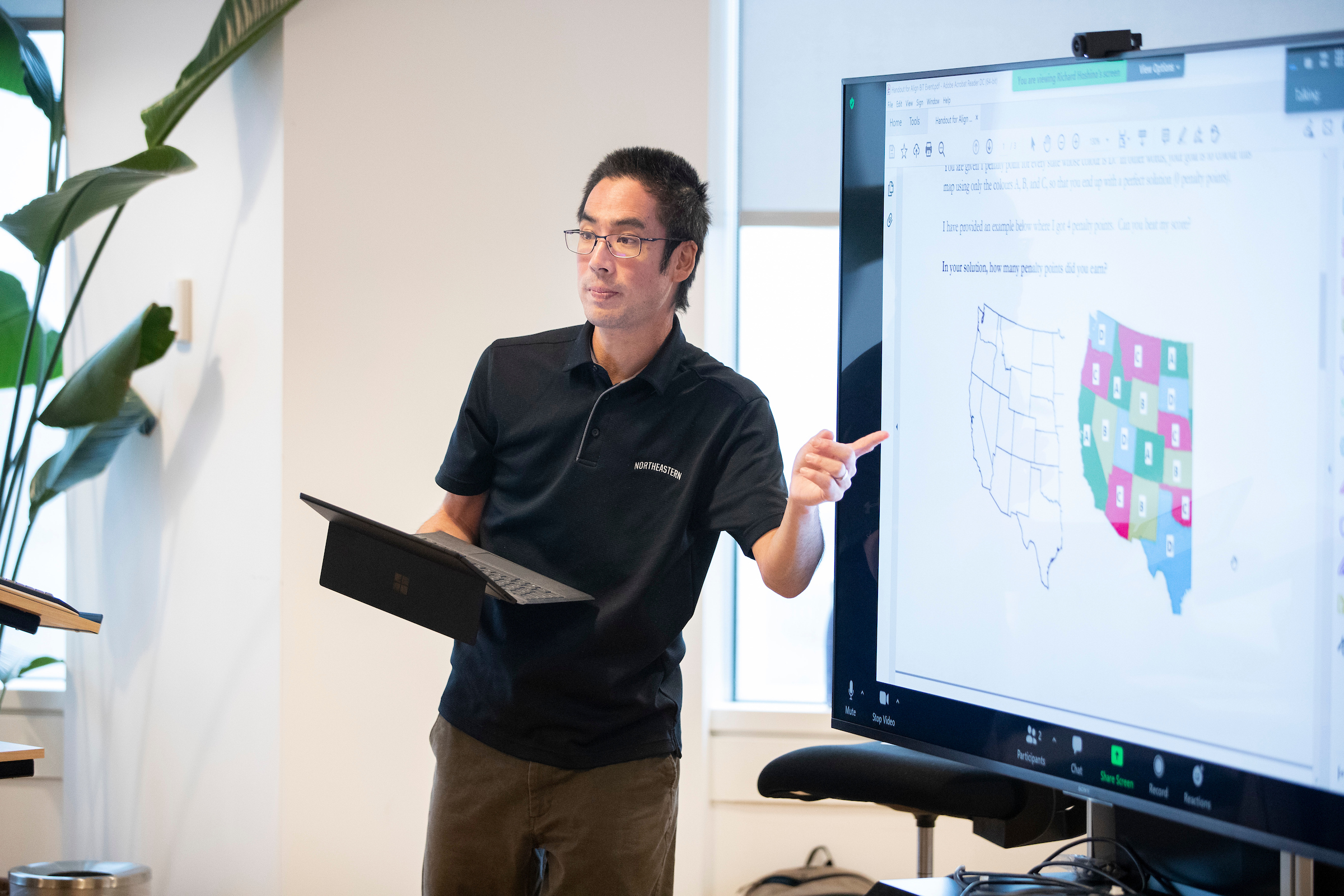

Hoshino’s creativity doesn’t stop at the classroom, though. He said, “By picking rich problems, we can teach an entire curriculum where students uncover the material for themselves, rather than a typical class where the teacher covers the material for the students.” He added, “I hate using the word ‘lecture.’ I call my classes ‘problem-solving workshops’ because I provide students with meaningful problems to tackle.”

In the process of solving those problems, Hoshino’s students uncover key concepts, techniques, and methods on their own.

“When I run workshops for teachers, they’re often looking for problems to share with their students so that they can teach in this way. So in these workshops, I actually give them the same problems that they would give their students to watch them work on them, wrestle with them, and argue the solutions together so that they can make the key discoveries themselves,” said Hoshino.

Inspired by his students’ backgrounds, professional experience, and academic experience, he gets a sense of fulfillment when he can help make the computer science field more inclusive. “The college’s mission, ‘computer science for all,’ doesn’t work if every single graduate of our program looks like me.”

Hoshino concluded, “Teaching at Northeastern has been rewarding, because so much of success in this program is about confidence. For these students, whether you believe you can or you can’t, you’re right.”